TechLetters Insight: new technologies of warfare - drones, and the practical realities and metrics of their employment

Aside from cyberoperations, drone use is one particular area of warfare technologies that undergo rapid evolution. Until now these tools were never applied on a large scale in complex environments under realistic battleground scenarios. No wonder there’s no actual data about drone performance. This led to the industry developing in arbitrary ways. Fortunately, we finally have some data . The excellent RUSI report “Preliminary Lessons in Conventional Warfighting from Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine: February–July 202” is not devoted to new technologies, but it is the first in the world concrete and practical assessment of drone use under realistic battleground scenarios. Many important conclusions can be drawn from it. It validates some previous intuitions and invalidates some other stances.

Words of caution.

The report is not specifically devoted to new technologies or drones (but it still has notable data).

Conflicts differ, just because a thing is/isn’t being used in a certain way under one scenario, doesn’t mean that the observations are definitive and must translate universally to other scenarios in the future.

Use of technology is a question of the technology, but also strategy, tactics, operations, the environment, the weather, etc. so a lot of variables.

How to use drones

Drones can be used in many ways. Preliminary wisdom may offer some initial assumptions. Drones or autonomous vehicles have sensors, and cameras, they might also have some autonomy capabilities. In civilian settings, they can be used to deliver postal messages or pizza, make pretty videos, or so. In battleground setups the same technologies can be reused for reconnaissance (ISR), aiding in targeting, and delivering lethal or destructive payloads (including explosives). Commercial off-the-shelf may (and are) used, specialized products as well.

The subsequent data and observations come from or are based on this report.

How drones are used in battlefields of the Russian war in Ukraine

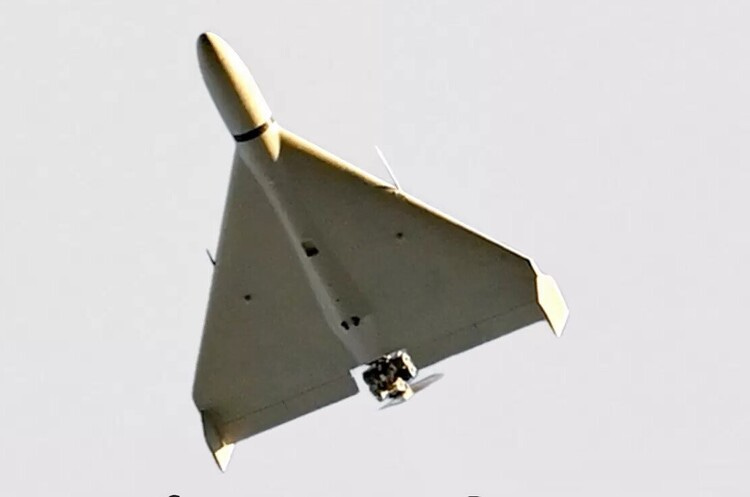

In Ukraine, unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs, drones) were used in target acquisition. Under heavy shelling, this is a huge risk to humans. UAVs allow area visibility and were used extensively. Commercial (adapted) quadcopters. "SKIF (UA), Orlan-10 (RU) ... were especially valuable because they could fly at medium altitude, were too cheap to be economical targets for air defences, and provided extensive imagery to enable rapid and responsive fires”

Metrics. Observations.

Most drones are quickly lost. Ultimately, 90% of UAVs are lost. Their lifetime is expectancy limited.

“attrition rates were extremely high. Of all UAVs used by the UAF in the first three phases of the war covered by this study, around 90% were destroyed. The average life expectancy of a quadcopter remained around three flights. The average life expectancy of a fixed-wing UAV was around six flights. Skilled crews who properly pre-programmed the flight path of their UAVs to approach targets shielded by terrain and other features could extend the life of their platforms”

What does it mean? They must be expandable. And available in large quantities.

Success is unobvious:

“even when UAVs survived, this did not mean that they were successful in carrying out their missions. UAVs could fail to achieve their missions because the requirements to get them in place – flying without transmitting data, with captured images to be downloaded on recovery, for example – prevented timely target acquisition before the enemy displaced”

The critical metric here. Only ~30% of UAV missions are “successful”:

“In aggregate, only around a third of UAV missions can be said to have been successful. Here, the Orlan-10 should be singled out in terms of its utility because the cheap platform nevertheless had high performance and proved difficult to counter, although its inertial navigation makes insufficient account of windage. Even the Russian military, however, found that it did not have enough of these platforms to sustain the loss rate during the battle in Donbas”

Russian drones were much ridiculed (a skillful information operation/propaganda?) at some point, but it seems that they may still be effective. As we’ve seen recently, Russia also tries to compensate with Iranian Shahed’s (“flying bombs” is maybe a more appropriate name than “kamikaze drones” or “loitering munitions”).

How to defend? “Given that loitering munitions targeting airfields, critical national infrastructure, and other targets are exceedingly small and low flying, elevated sensors such as the AESA radar of the F-35 are ideal for detecting these targets. At the same time, the allocation of F-35s against such targets would be an entirely inappropriate use of the platform“.

The defence must be done using cheap and specialised counter-drone technology, primarily with electronic warfare.Indeed, the report mentions that the use of drones in an environment of electronic warfare (i.e. jamming) is difficult.

Takeaways

What does it mean? Drones are very useful in defence and in offence. But it is critical to have a lot of them (large quantities. This means that they must be cheap. As we know now, UAVs can also be used to saturate the operation of anti-air systems. It’s when a large number (high quantity!) overloads the defence capability. That’s the point. Imagine how to defend a city from 10.000 approaching loitering munitions. It makes completely no sense to expend expensive weapons against something cheap and in big quantities. Expensive ammunition will run out fast, and this can be seized by the aggressor.

That is a strategy in itself: quantity becomes quality, as would Marx say.

They also “must be available at scale”, and “a large number of troops are required to know how to use these tool”. For this reason: ”the rate of consumption of these capabilities demands that they are ruthlessly simplified and rationalised so that they can be produced at scale and cheaply”.

What to do, what to not do

That would mean that developing and using a few of expensive setups would be inappropriate use of this technology, at least if this was the sole use.

It is probably also a good idea to have a proper jailbreak capability to reflash the firmware of commercial drones to disable the built-in limits of things like speed, altitude, or geofence. To this date, there was no indication of such things being done by Ukraine or Russia, aside from that we know that firmware may have been specially prepared (but not much data about this in public).

Decisional speed matters, hierarchical units are considered harmful

But there’s also this from the conclusions: “Requiring higher-echelon approval will make the employment of UAS uncompetitively slow. Requiring units to follow the procedures for aircraft in launching UAS also means that it is inordinately expensive to train UAS operators and this too becomes a constraint on their employment that means tactical units will not have enough pilots to keep up the required number of orbits to be competitive. For the UK, the implication is that UAS need to be classified as munitions rather than aircraft.”

In other words, the decision tree must be extremely simplified, or else the primary advantage of drone use – speed – is lost. And then a lot more can be lost.

Wars are about control - you ultimately do this with land units

I’ll end with a quote from the report about armor use, so you get the perspective right:

“The role and significance of armour in the conflict must be underpinned by an understanding of the tactical evolution of its employment over the past eight years and the scale at which armour is fielded by the UAF. Counting the two regular and four reserve tank brigades, tank units of mechanised and mountain brigades, as well as brigades of marines and air-assault troops, the UAF fielded about 30 tank battalions at the start of the conflict. A significant part of these tank units was formed between 2014 and 2018, for which 500 tanks were delivered to the UAF. The total number of Ukrainian main battle tanks at the time of the invasion was about 900. For comparison, the Russian armed forces had 2,800 combat-ready tanks in their invasion force, and Russian proxies in Donbas fielded about 400”

Drones offer important specialised capabilities. But just like ‘normal’ air or sea units, you cannot decisively attack or defend using this. You cannot win a war with drones, cyberattacks, too. It’s done with land units.

And this:

“there has been abundant debate over whether the war proves the utility or obsolescence of various military systems: loitering munitions versus artillery, or ATGWs versus tanks. These debates are largely nugatory. Legacy systems, from T-64 tanks to BM-21 Grad MLRS have proven instrumental in Ukraine’s survival. That does not mean, however, that historical concepts of employment for these systems remain advisable“.

This is probably about “not fighting the previous war”.

Ultimate conclusion

That is probably the most important technology-wise conclusion here.

Lots of drones. Cheap. Easy to use. With simple decision modes.

Did you like the assessment and analysis? Any questions, comments, complaints, or offers of engagement ? Feel free to reach out: me@lukaszolejnik.com