TechLetters Insights: Quantum computer export controls (Waasenaar) - do they make sense in 2025?

In 2024, countries began issuing export controls on quantum computers, designating them as ‘dual-use’ products. A dual-use product refers to items, including software and technology, that can be used for both civil and military purposes. The export controls are based on performance metrics: qubit sizes and error rates. To perform useful computations, quantum computers must attain a specific number of controlled qubits with low error rates; otherwise, reliable computations are not possible.

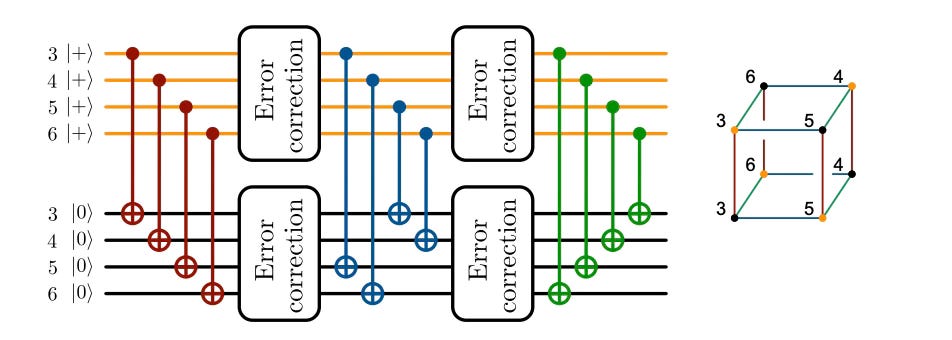

A physical qubit is a basic unit of quantum information that cannot perform quantum computations on its own; logical qubits are necessary for effective computations. However, to attain logical qubits, error rates must be kept sufficiently low. As a reference, the export controls mention the universal C-NOT gate operations — such gates can be used to perform quantum computations utilizing quantum algorithms. That’s a good choice because since C-NOT is a universal gate, it can be used to implement any algorithm.

Here’s data based on controls in Canada, France, UK. The performance metrics are the same which implies an underlying policy/diplomatic coordination process.

34–100 qubits: C-NOT gate error ≤ 0.01% ( less than or equal 10⁻⁴)

100–200 qubits: C-NOT gate error ≤ 0.1% (10⁻³)

200–350 qubits: C-NOT gate error ≤ 0.2% (2 × 10⁻³)

350–500 qubits: C-NOT gate error ≤ 0.3% (3 × 10⁻³)

500–700 qubits: C-NOT gate error ≤ 0.4% (4 × 10⁻³)

700–1,100 qubits: C-NOT gate error ≤ 0.5% (5 × 10⁻³)

1,100–2,000 qubits: C-NOT gate error ≤ 0.6% (6 × 10⁻³)

2,000+ qubits

The 2000+ qubits limit may be understandable, but why limiting, say, 34 qubits with very low error rates?

In 2024 there were no quantum computers capable of usable computations, so the export control look likely theoretical or considers a possibility of rapid advance. These export controls are either an element of tightening controls, or someone may know something or expects those rapid advances.

For reference, here’s a Microsoft/Quantinuum demonstration of a quantum computer made from 16 physical qubits with two-qubit gate error 1.15(5) × 10⁻³ (0.115%).

This means that such a quantum computer would not be subject to export control rules.

How to measure performance?

There’s a need to develop independent benchmarking capability (metrics are not yet agreed) to see where the development is at this moment. In principle, one such benchmarking could be the efficiency in integer factorisation. It would not, however, be very informative as a full run of Shor’s algorithm so far achieved a success to factor the integer 35.

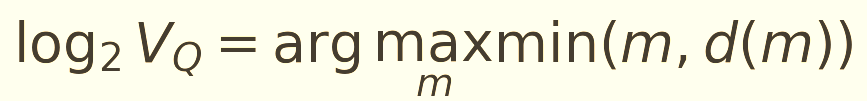

Quantum volume measures how powerful a quantum computer is by considering the number of qubits and how well they work together. It is calculated based on the problem size (number of qubits) a quantum computer can handle with accurate computations, considering errors, connectivity, and reliability.

where: V_{Q} is the quantum volume, m is the number of qubits used in the computation, d(m) is the maximum depth of a quantum circuit that can be reliably executed with mm qubits.

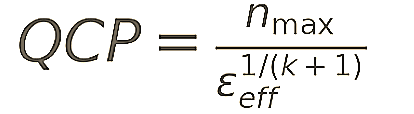

However, perhaps it’s all an overkill? Let’s introduce something else.

n_max being the number of usable qubits (bigger - better).

ϵ_eff is the effective error rate (lower - better).

k = Algorithm complexity factor (1 for simple, higher for complex problems; for example k=2 for Quantum Fourier transform. k=3 for Shor’s algorithms, etc.).

If errors are low, QCP≈n_max (more qubits = better). If errors are high, QCP decreases (errors limit performance). Higher QCP means a better quantum computer for real-world tasks.

The Quantinuum system mentioned previously has a QCP score ~87 but lacks sufficient number of qubits to even run Shor’s algorithm. Factoring a 2048-bit RSA key requires ~819,200 QCP score, ~10,000× more, and 1,700—6,152 logical qubits. To achieve this with error correction at a 10⁻³ error rate, a quantum computer would need 17 to 61.5 trillion physical qubits. The best export-controlled system (34–100 qubits, 0.01% error) has a score of ~670 QCP, while the largest (1,100–2,000 qubits, 0.6% error) reaches ~2,785 QCP. Even the most powerful allowed system is millions of times too weak to break RSA-2048. So why bother with export controls today?

Summary

In the next 5 years, export controls based on metrics like qubit count and gate efficiency are precautionary than reactive. Current systems are firmly in the NISQ region with no clear path forward. A large-scale, programmable quantum computer remains a long-term, hypothetical prospect. There are no convincing developments indicating that such export controls issued today are justified. However, they still did appear for some reason.